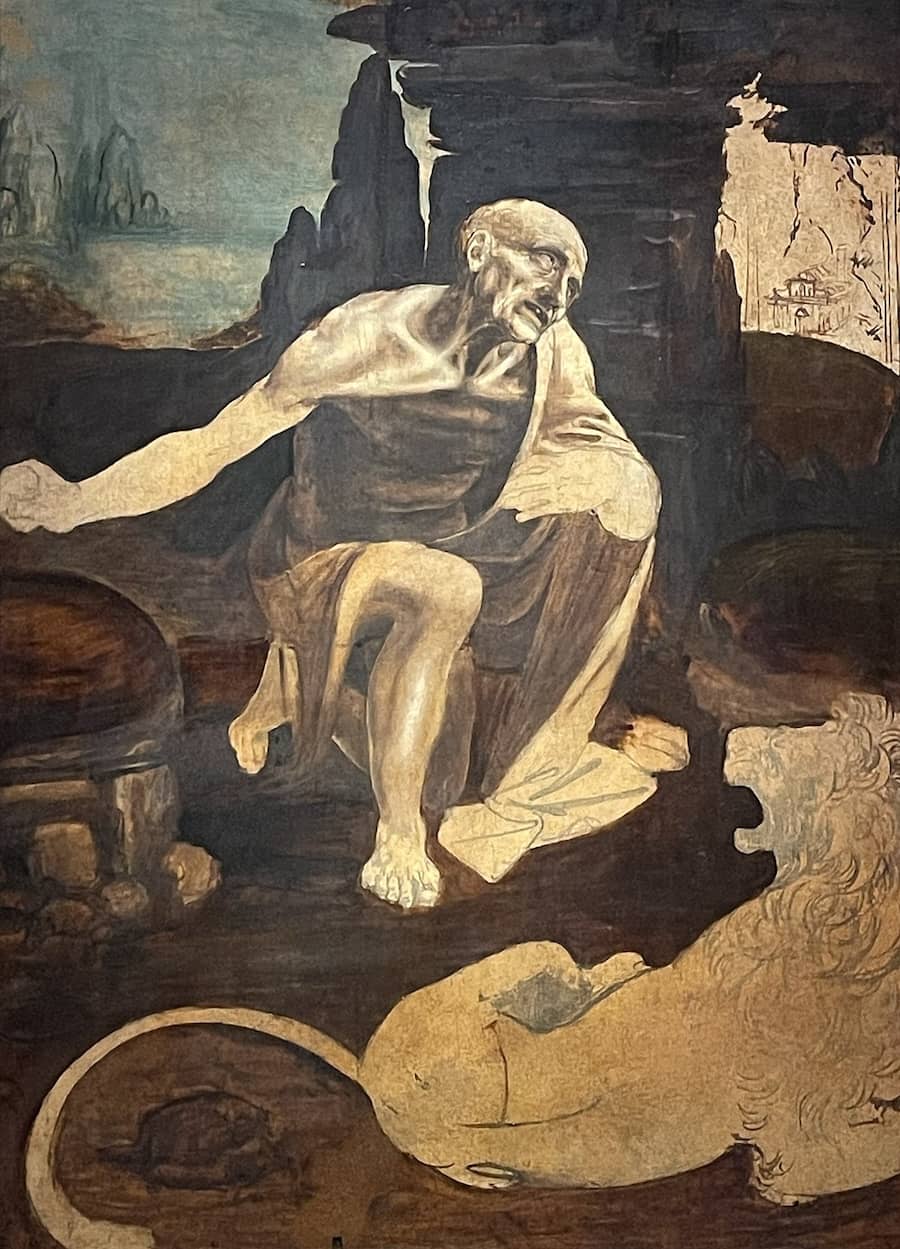

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness - by Leonardo da Vinci

It was during a difficult period in his life, just prior to departing for Milan in 1482, that Leonardo worked on his most tragic painting and yet another destined to remain unfinished. He was a man often subject to bouts of melancholy; notes in his diary show how low he was feeling at this time in his life. Comments found in the margin of the Codex Atlanticus: "Why do you suffer so? The greater one is, the greater grows one's capacity for suffering. I thought I was learning to live; I was only learning to die."

Jerome's imploring face is at a three-quarter angle; it is haggard from fasting and penitence; at the same time, his eyes display determination and will-power. In his outstretched right hand, he clasps a rock, the penitent about to strike his own breast. Making this all the more dramatic is the setting of the subject against the dark background of a cave. Off to one side, another of Leonardo's rocky landscapes rises into the mist.

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness is a wonderful pictorial presentation of the artist's emotional turmoil during that period. It is also notable for how well it demonstrates Leonardo's anatomical knowledge. The saint's muscles and bones are covered with a thin layer of flesh, with cheek and neck muscles being accurately drawn.

The story of this painting is a little unbelievable, but as interesting as one could hope for. Originally in the Vatican collection, it passed into the hands of Angelica Kaufmann. Supposedly it was then mislaid and someone cut it into two pieces. One section was converted into a table top while a shoemaker used the other portion for the upper part of a stool. Joseph Cardinal Fesch recognised the table painting in 1820; it is assumed he had already seen a drawing of the work somewhere. He purchased it from the Roman junk shop hoping to locate the missing segment, something he succeeded in doing several years afterwards. The painting was restored though obvious evidence of the cut out section can still be clearly seen. Heirs of Napoleon Bonaparte's uncle (Cardinal Fesch) later sold the ochre groundwork for twenty-five francs to Pope Pius IX; it was then placed back into the care of the Vatican where it still resides today.

This is one of the very few paintings attributed to Leonardo over which there has never been any question. No contemporary references to the work have been found yet it is considered unmistakably his painting methods and structure; the similarity to Adoration of the Magi is also obvious.