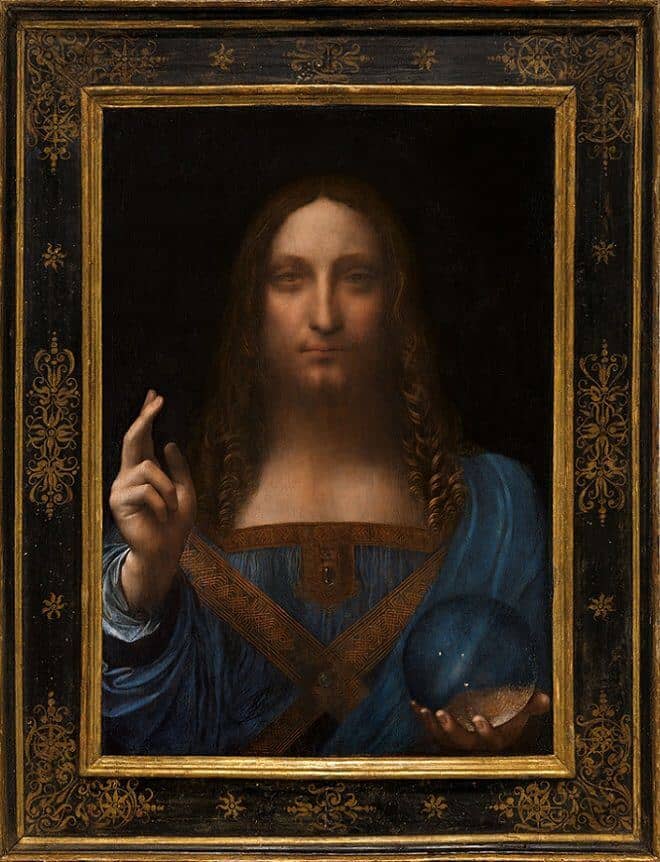

Salvator Mundi - by Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo paints Salvator Mundi possibly for King Louis XII of France and his consort, Anne of Brittany. It is most likely commissioned soon after the conquests of Milan and Genoa.

The 26-inch haunting oil-on-panel painting depicts a half-length figure of Christ as Savior of the World, facing front and dressed in Renaissance-era robes. In his painting, Leonardo presents Christ as he is characterized in the Gospel of John 4:14: 'And we have seen and testify that the Father has sent his Son as the Saviour of the World.' Christ gazes fixedly at the spectator, lightly bearded with auburn ringlets, holding a crystal sphere in his left hand and offering benediction with his right.

Salvator Mundi was at once time believed to have been destroyed. The painting disappeared from 1763 until 1900, when it was bought by Sir Charles Robinson as a work by Bernardino Luini, a follower of Leonardo. It next appeared at a Sotheby's in England in 1958 where it sold for £45 - about $125 at the time. It then disappeared again until it was bought at a small U.S. auction house in 2005.

Like many of Leonardo's surviving works, the painting was not in mint condition when it resurfaced in the early 2000s. It required extensive restoration. Even though there are some respected experts on Renaissance art who question the attribution of the painting to Leonardo, it was sold at auction at Christie's in New York in November 2017 for $450,312,500, a new record price for an artwork. The purchaser was not disclosed.

The Mystery of the Orb

Art scholars agree that the glass orb in the painting symbolizes the world. However, the orb does not refract light in the way an actual glass sphere would. Some art historians believe this proves that da Vinci did not paint the work.

Evidence shows that the Italian master had studied the science of optics. He left behind copious notes and diagrams on the subject. So, if he were painting a solid glass orb, Leonardo da Vinci would show the true distortion of objects behind curved glass.

In another explanation for the mystery of da Vinci's orb, biographer Walter Isaacson speculates that omitting distortion was the artist's conscious choice. In bypassing the natural laws of optics, he says, da Vinci meant to show the miraculous nature of his subject matter. Martin Kemp, another da Vinci scholar, describes the anomaly of the sphere as a matter of religious etiquette. He thinks da Vinci did not want to distort a portrait of Christ.

A recent study by Computer scientists from the University of California, Irvine proffers another, more believable explanation. They used digital graphics and light simulation programs to prove that da Vinci's rendering of the glass sphere is accurate after all.

The team asserts that the sphere da Vinci painted has to be hollow glass rather than a solid crystal. As such, it would not distort the light as others have assumed it should. Rather, it would cause only slight distortions of the drapery behind it, which the artist painted accurately.

This finding jibes more closely with da Vinci's fascination with science. As shown by the team's sophisticated graphic renderings, Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi incorporates his scientific knowledge of optics rather than belies it.